(see bottom for assigned readings and questions)

Attention, Transformers, and BERT

Monday, 28 August

Transformers1 are a class of deep learning models that have revolutionized the field of natural language processing (NLP) and various other domains. The concept of transformers originated as an attempt to address the limitations of traditional recurrent neural networks (RNNs) in sequential data processing. Here’s an overview of transformers’ evolution and significance.

Background and Origin

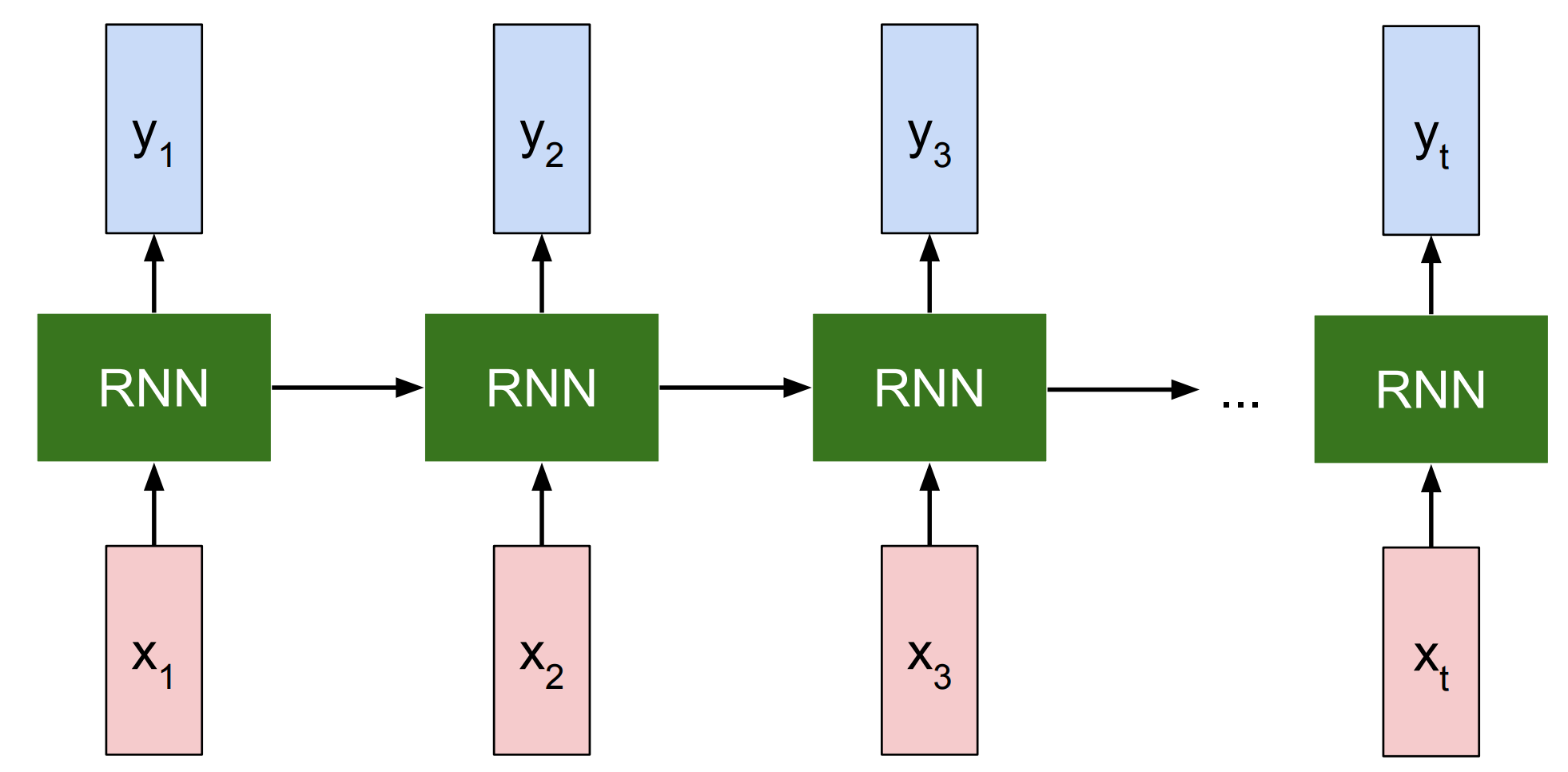

RNNs2 were one of the earliest models used for sequence-based tasks in machine learning. They processed input tokens one after another and used their internal memory to capture dependencies in the sequence. The following figure gives an illustration of the RNN architecture.

RNN (Image Source)

Limitations of RNNs. Despite many improvements over this basic architecture, RNNs have the following shortcomings:

- RNNs struggle with long sequences. It only keeps recent information but looses long-term memory.

- RNNs suffer from vanishing gradients3. In this, the gradients that are used to update the model become very small during back propagation, leading the RNNs to learn nothing from training.

Introduction of LSTMs. Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM)4 networks were then introduced to address the vanishing gradient problem in RNNs. LSTMs had memory cells and gating mechanisms that allowed them to capture long-term memories more effectively. While LSTMs improved memory retention, they were still computationally expensive and slow to train, especially on large datasets.

Attention Mechanism. The attention mechanism561 was introduced as a way to help models focus on relevant parts of the input sequence when generating output. This addressed the memory issues that plagued previous models. Attention mechanisms allowed models to weigh the importance of different input tokens when making predictions or encoding information. In essence, it enables the model to focus selectively on relevant parts of the input sequence while disregarding less pertinent ones. In practice, attention mechanism can be categorized into self-attention and multi-head attention based on the number of heads used in the attention structure.

The Transformer Model

The transformer architecture, introduced by Vaswani et al. (2017) 1, marked a significant advance in NLP. It used self-attention mechanisms to process input tokens in parallel and capture contextual information more effectively. Transformers broke down sentences into smaller parts and learned statistical relationships between these parts to understand meaning and generate responses. The model utilized input embeddings to represent words and positional encodings to address the lack of inherent sequence information. The core innovation was the self-attention mechanism, which allowed tokens to consider their relationships with all other tokens in the sequence

Benefits of Transformers. Transformers can capture complex contextual relationships in language, making them highly effective for a wide range of NLP tasks. The parallel processing capabilities of transformers, enabled by self-attention, drastically improved training efficiency and reduced the vanishing gradient problem.

Mathematical Foundations. Transformers involve mathematical representations of words and their relationships. The model learns to establish connections between words based on their contextual importance.

Crucial Role in NLP. Transformers play a crucial role in capturing the meaning of words and sentences78, allowing for more accurate and contextually relevant outputs in various NLP tasks. In summary, transformers, with their innovative attention mechanisms, have significantly advanced the field of NLP by enabling efficient processing of sequences, capturing context effectively, and achieving state-of-the-art performance on a variety of tasks.

Advancements in Transformers. One significant advancement of transformers over previous models like LSTMs and RNNs is their ability to handle long-range dependencies and capture contextual information more effectively. Transformers achieve this through self-attention and multi-head attention. This allows them to process input tokens in parallel, rather than sequentially, leading to improved efficiency and performance. However, a drawback could be increased computational complexity due to the parallel processing, especially in multi-head attention.

Positional Encodings. The use of positional encodings in transformers helps address the lack of inherent positional information in their architecture. This enables transformers to handle sequential data effectively without relying solely on the order of tokens. The benefits include scalability and the ability to handle longer sequences, but a potential drawback is that these positional encodings might not fully capture complex positional relationships in very long sequences.

Self-Attention and Multi-Head Attention. Self-attention is a useful mechanism that allows each token to consider the relationships between all other tokens in a sequence. While it provides a more nuanced understanding of input, it can be computationally expensive. The use of multi-head attention further enhances the model’s ability to capture different types of dependencies in the data. The number of attention heads (e.g., 8 in BERT) is a balance between performance and complexity. Too few or too many heads can result in suboptimal performance. More details about self-attention and multi-head attention can be found in 9.

Context and Answers in Activities. Let’s do some activity now!

I used to ___

Yesterday, I went to ___

It is raining ___

The context given in the activities influences the answers provided. More context leads to more accurate responses. This highlights how models like BERT benefit from bidirectional attention, as they can consider both preceding and succeeding words when generating predictions.

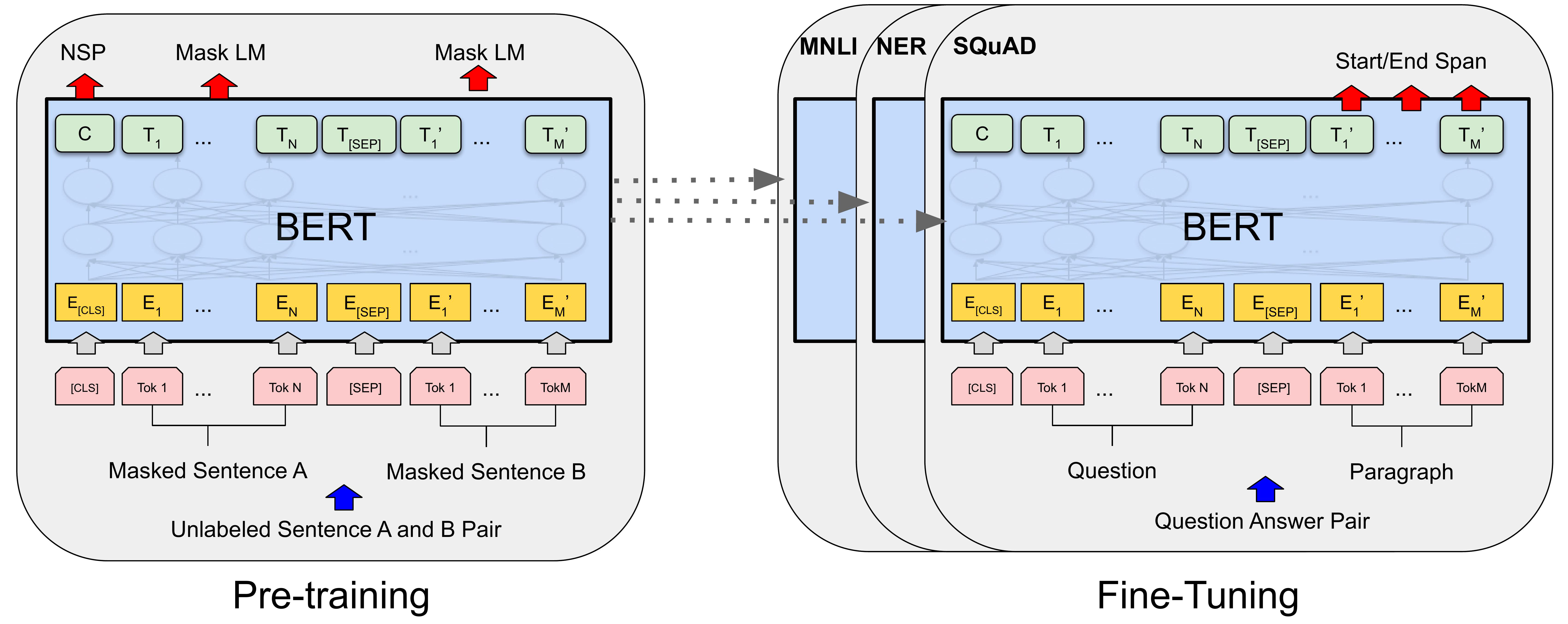

BERT: Bidirectional Transformers

BERT’s Design and Limitations. BERT10 uses bidirectional attention and masking to enable it to capture context from both sides of a word. The masking during training helps the model learn to predict words in context, simulating its real-world usage. While BERT’s design was successful, it does require a substantial amount of training data and resources. Its application may be more focused on tasks such as sentiment analysis, named entity recognition, and Question answering, while GPT is better at handling tasks such as content creation, text summarization, and machine translation11.

Future Intent of BERT Authors. The authors of BERT might not have fully anticipated its exact future use and impact. While they likely foresaw its usefulness, the swift and extensive adoption of language models across diverse applications likely surpassed their expectations. The increasing accessibility and scalability of technology likely contributed to this rapid adoption. As mentioned by the professor in class, the decision to publish something in industry (and at Google in particular) often depends on its perceived commercial value. If Google were aware of the future commercial value of transformers and the methods introduced by BERT, they may not have published these papers openly (although this is purely speculation without any knowledge of the internal process that might have been followed to publish these papers).

Discussion Questions

Q: What makes language models different from transformers?

A language model encompasses various models that understand language, whereas transformers represent a specific architecture. Language models are tailored for natural languages, while transformers have broader applications. For example, transformers can be utilized in tasks beyond language processing, such as predicting protein structures from genomic sequences (as done by AlphaFold).

Q: Why was BERT published in 2019, inspiring large language models, and why have GPT models continued to improve while BERT’s advancements seem comparatively limited?

Decoder models, responsible for generating content, boast applications that are both visible and instantly captivating to the public. Examples like chatbots, story generators, and models from the GPT series showcase this ability by producing human-like text. This immediate allure likely fuels increased research and investment. Due to the inherent challenges in producing coherent and contextually appropriate outputs, generative tasks have garnered significant research attention. Additionally, decoder models, especially transformers like GPT-212 and GPT-313, excel in transfer learning, allowing pre-trained models to be fine-tuned for specific tasks, highlighting their remarkable adaptability.

Q: Why use 8-headers in the transformer architecture?

The decision to use 8 attention heads is a deliberate choice that strikes a balance between complexity and performance. Having more attention heads can capture more intricate relationships but increases computational demands, whereas fewer heads might not capture as much detail.

Q: BERT employs bidirectional context to pretrain its embeddings, but there is debate about whether this approach genuinely captures the entirety of language context?

The debate arises from the fact that while bidirectional context is powerful, it might not always capture more complex contextual relationships, such as those involving long-range dependencies or nuanced interactions between distant words. Some argue that models with other architectures or training techniques might better capture such intricate language nuances.

Wednesday: Training LLMs, Risks and Rewards

In the second class discussion, the team talked about LLMs and tried to make sense of how they’re trained, where they get their knowledge, and where they’re used. Here’s what they found out.

How do LLMs become so clever?

Before LLMs become language wizards, they need to be trained. The crucial question is where they acquire their knowledge.

LLMs need lots and lots of information to learn from. They look at stuff like internet articles, books, and even Wikipedia. But there’s a catch. They have a clean-up crew called “C4” to make sure the information is tidy and reliable.

Training LLMs requires potent computational resources, such as Graphics Processing Units (GPUs). Computationally-expensive large-scale training, while crucial for enhancing their capabilities, involves substantial energy consumption, which, depending on how it is produces may emit large amounts of carbon dioxide.

Transitioning to the practical applications of these language models, LLMs excel in diverse domains14. They can undergo meticulous fine-tuning to perform specialized tasks, ranging from aiding in customer service to content generation for websites. Furthermore, these models exhibit the ability to adapt and learn from feedback, mirroring human learning processes.

Risks and Rewards

In our class discussion, we had a friendly debate about LLMs. Some students thought they were fantastic because they can boost productivity, assist with learning, and bridge gaps between people. They even saw LLMs as potential problem solvers for biases in the human world.

But others had concerns. They worried about things like LLMs being too mysterious (like a black box), how they could influence the way people think, and the risks of false information and deep fakes. Some even thought that LLMs might detrimentally impact human intelligence and creativity.

In our debate, there were some interesting points made:

Benefits Group.

- LLMs can enhance creativity and accelerate tasks.

- They have the potential to facilitate understanding and learning.

- Utilizing LLMs may streamline the search for ideas.

- LLMs offer a tool for uncovering and rectifying biases within our human society. Unlike human biases, there are technical approaches to mitigate biases in models.

Risks Group.

- Concerns were expressed regarding LLMs’ opacity and complexity, making them challenging to comprehend.

- Apprehensions were raised about LLMs potentially exerting detrimental influences on human cognition and societal dynamics.

- LLMs are ripe for potential abuses in their ability to generate convincing false information cheaply.

- The potential impact of LLMs on human intelligence and creativity was a topic of contemplation.

After the debate, both sides had a chance to respond:

Benefits Group Rebuttals.

- Advocates pointed out that ongoing research aims to enhance the transparency of LLMs, reducing their resemblance to black boxes.

- They highlighted collaborative efforts directed at the improvement of LLMs.

- The significance and potential of LLMs in domains such as medicine and engineering was emphasized.

- Although the ability of generative AI to produce art in the style of an artist is damaging to the career of that artist, it is overall beneficial to society, enabling many others to create desired images.

- Addressing economic concerns, proponents saw LLMs as catalysts for the creation of new employment opportunities and enhancers of human creativity.

Risks Group Rebuttals.

- They noted the existence of translation models and the priority of fairness in AI.

- Advocates asserted that LLMs can serve as tools to identify and mitigate societal biases.

- The point was made that AI can complement, rather than supplant, human creativity.

- Although generating AI art may have immediate benefits to its users, it has long term risks to our culture and society if individuals are no longer able to make a living as artists or find the motivation to learn difficult skills.

Wrapping It Up. So, there you have it, a peek into the world of Large Language Models and the lively debate about their pros and cons. As you explore the world of LLMs, remember that they have the power to be amazing tools, but they also come with responsibilities. Use them wisely, consider their impact on our world, and keep the discussion going!

Readings

Introduction to Large Language Models (from Stanford course)

Ashish Vaswani, Noam Shazeer, Niki Parmar, Jakob Uszkoreit, Llion Jones, Aidan N. Gomez, Lukasz Kaiser, Illia Polosukhin. Attention Is All You Need. https://arxiv.org/abs/1706.03762. NeurIPS 2017.

These two blog posts by Jay Alammar are not required readings but may be helpful for understanding attention and Transformers:

- Visualizing A Neural Machine Translation Model (Mechanics of Seq2seq Models With Attention)

- The Illustrated Transformer

Jacob Devlin, Ming-Wei Chang, Kenton Lee, Kristina Toutanova. BERT: Pre-training of Deep Bidirectional Transformers for Language Understanding. ACL 2019.

Laura Weidinger, John Mellor, Maribeth Rauh, Conor Griffin, Jonathan Uesato, Po-Sen Huang, Myra Cheng, Mia Glaese, Borja Balle, Atoosa Kasirzadeh, Zac Kenton, Sasha Brown, Will Hawkins, Tom Stepleton, Courtney Biles, Abeba Birhane, Julia Haas, Laura Rimell, Lisa Anne Hendricks, William Isaac, Sean Legassick, Geoffrey Irving, Iason Gabriel. Ethical and social risks of harm from Language Models DeepMind, 2021. https://arxiv.org/abs/2112.04359

Optional Additional Readings:

Center for Research on Foundation Models (CRFM) at the Stanford Institute for Human-Centered Artificial Intelligence (HAI). On the Opportunities and Risks of Foundation Models

Matthew E. Peters, Mark Neumann, Mohit Iyyer, Matt Gardner, Christopher Clark, Kenton Lee, and Luke Zettlemoyer. 2018. Deep Contextualized Word Representations. Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics, 2018.

GPT1: Alec Radford, Karthik Narasimhan, Tim Salimans, and Ilya Sutskever. Improving language understanding by generative pre-training. 2018.

GPT2: Alec Radford, Jeffrey Wu, Rewon Child, David Luan, Dario Amodei, and Ilya Sutskever. Language models are unsupervised multitask learners, 2019.

GPT3: Tom B. Brown, Benjamin Mann, Nick Ryder, Melanie Subbiah, Jared Kaplan, Prafulla Dhariwal, Arvind Neelakantan, Pranav Shyam, Girish Sastry, Amanda Askell, Sandhini Agarwal, Ariel Herbert-Voss, Gretchen Krueger, Tom Henighan, Rewon Child, Aditya Ramesh, Daniel M. Ziegler, Jeffrey Wu, Clemens Winter, Christopher Hesse, Mark Chen, Eric Sigler, Mateusz Litwin, Scott Gray, Benjamin Chess, Jack Clark, Christopher Berner, Sam McCandlish, Alec Radford, Ilya Sutskever, and Dario Amodei. Language models are few-shot learners, 2020.

Discussion Questions

Before 5:29pm on Sunday, August 27, everyone who is not in either the lead or blogging team for the week should post (in the comments below) an answer to at least one of these three questions in the first section (1–3) and one of the questions in the section section (4–7), or a substantive response to someone else’s comment, or something interesting about the readings that is not covered by these questions.

Don’t post duplicates - if others have already posted, you should read their responses before adding your own.

Questions about “Attention is All You Need” and “BERT: Pre-training of Deep Bidirectional Transformers for Language Understanding”:

-

Many things in the paper (especially “Attention is All You Need”) seem mysterious and arbitrary. Identify one design decision described in the paper that seems arbitrary, and possible alternatives. If you can, hypothesize on why the one the authors made was selected and worked.

-

What were the key insights that led to the Transformers/BERT design?

-

What is something you don’t understand in the paper?

===

Questions about “Ethical and social risks of harm from Language Models”

-

The paper identifies six main risk areas and 21 specific risks. Do you agree with their choices? What are important risks that are not included in their list?

-

The authors are at a company (DeepMind, part of Google/Alphabet). How might their company setting have influenced the way they consider risks?

-

This was written in December 2021 (DALL-E was released in January 2021; ChatGPT was released in November 2022; GPT-4 was released in March 2023). What has changed since then that would have impacted perception of these risks?

-

Because training and operating servers typically requires fresh water and fossil fuels, how should we think about the environmental harms associated with LLMs?

-

The near and long-term impact of LLMs on employment is hard to predict. What jobs do you think are vulnerable to LLMs beyond the (seemingly) obvious ones mentioned in the paper? What are some jobs you think will be most resilient to advances in AI?

-

Vaswani, A., Shazeer, N., Parmar, N., Uszkoreit, J., Jones, L., Gomez, A. N., … & Polosukhin, I. (2017). Attention is all you need. Advances in neural information processing systems, 30. ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎

-

Sherstinsky, A. (2020). Fundamentals of recurrent neural network (RNN) and long short-term memory (LSTM) network. Physica D: Nonlinear Phenomena, 404, 132306. ↩︎

-

Pascanu, R., Mikolov, T., & Bengio, Y. (2013, May). On the difficulty of training recurrent neural networks. In International conference on machine learning (pp. 1310-1318). Pmlr. ↩︎

-

Hochreiter, S., & Schmidhuber, J. (1997). Long short-term memory. Neural computation, 9(8), 1735-1780. ↩︎

-

Mnih, V., Heess, N., & Graves, A. (2014). Recurrent models of visual attention. Advances in neural information processing systems, 27. ↩︎

-

Bahdanau, D., Cho, K., & Bengio, Y. (2014). Neural machine translation by jointly learning to align and translate. arXiv preprint arXiv:1409.0473. ↩︎

-

Lin, T., Wang, Y., Liu, X., & Qiu, X. (2022). A survey of transformers. AI Open. ↩︎

-

Khan, S., Naseer, M., Hayat, M., Zamir, S. W., Khan, F. S., & Shah, M. (2022). Transformers in vision: A survey. ACM computing surveys (CSUR), 54(10s), 1-41. ↩︎

-

Karim, R. (2023, January 2). Illustrated: Self-attention. Medium. https://towardsdatascience.com/illustrated-self-attention-2d627e33b20a ↩︎

-

Devlin, J., Chang, M. W., Lee, K., & Toutanova, K. (2018). Bert: Pre-training of deep bidirectional transformers for language understanding. arXiv preprint arXiv:1810.04805. ↩︎

-

Ahmad, K. (2023b, April 26). GPT vs. Bert: What are the differences between the two most popular language models?. MUO. https://www.makeuseof.com/gpt-vs-bert/ ↩︎

-

Radford, A., Wu, J., Child, R., Luan, D., Amodei, D., & Sutskever, I. (2019). Language models are unsupervised multitask learners. OpenAI blog, 1(8), 9. ↩︎

-

Brown, T., Mann, B., Ryder, N., Subbiah, M., Kaplan, J. D., Dhariwal, P., … & Amodei, D. (2020). Language models are few-shot learners. Advances in neural information processing systems, 33, 1877-1901. ↩︎

-

Yang, J., Jin, H., Tang, R., Han, X., Feng, Q., Jiang, H., … & Hu, X. (2023). Harnessing the power of llms in practice: A survey on chatgpt and beyond. arXiv preprint arXiv:2304.13712. ↩︎