(see bottom for assigned readings and questions)

Prompt Engineering (Week 3)

- (Monday, 09/11/2023) Prompt Engineering

- Warm-up questions

- What is Prompt Engineering?

- How is prompt-based learning different from traditional supervised learning?

- In-context learning and different types of prompts

- What is the difference between prompts and fine-tuning?

- When is the best to use prompts vs fine-tuning?

- Risk of Prompts

- Discussion about Prompt format

- (Wednesday, 09/13/2023) Prompt Engineering: Exposing LLM Risks

- Readings

(Monday, 09/11/2023) Prompt Engineering

Warm-up questions

Monday’s class started with warm-up questions to demonstrate how prompts can help an LLM produce correct answers or desired outcomes. The questions and the prompts were tested in GPT3.5. This task was performed as an in-class experiment where each individual used GPT3.5 to test the questions and help GPT3.5 produce correct answers via prompts.

The three questions were:

- What is 7084 times 0.99?

- I have a magic box that can only transfer coins. If you insert a number of coins in it, the next day each coin will turn into two apples. If I add 10 coins and wait for 3 days, what will happen?

- Among “Oregon, Virginia, Wyoming”, what is the word that ends with “n”?

While the first question tested the arithmetic capability of the model, the second and the third questions tested common sense and symbolic reasoning, respectively. The initial response from GPT3.5 for all three questions was wrong.

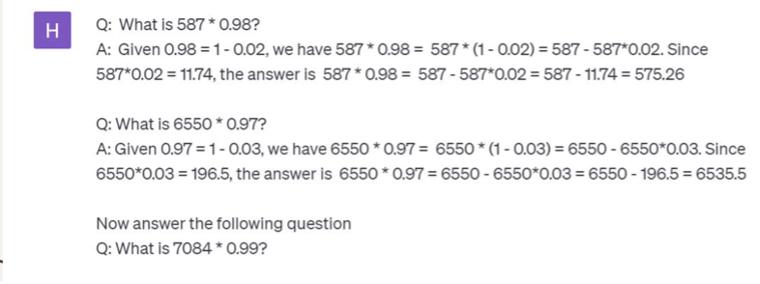

For the first question, providing more examples as prompts did not work. At the same time, an explanation of how to reach the specific answer by decomposing the multiplication into multiple steps helped.

Figure 1 shows the prompting for the first question and the answer from GPT3.5.

|

|

| Figure 1: Prompting for arithmetic question | |

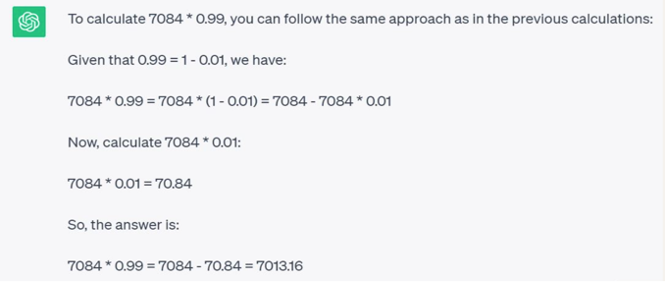

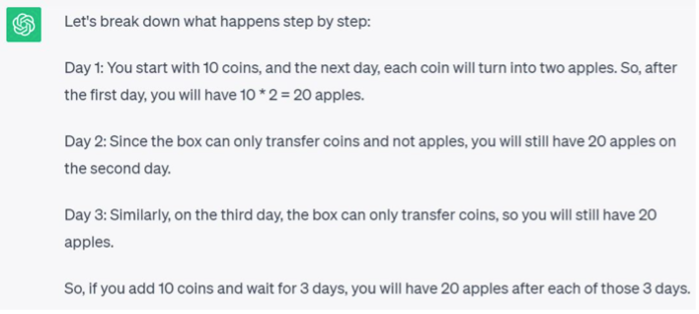

For the second question, providing an example and an explanation behind the reasoning on how to reach the final answer helped GPT produce the correct answer. Here, the prompt included explicitly stating that the magic box can also convert from coins to apples.

Figure 2 shows the prompting for the second question and the answer from GPT3.5.

|

|

| Figure 2: Prompting for common sense question | |

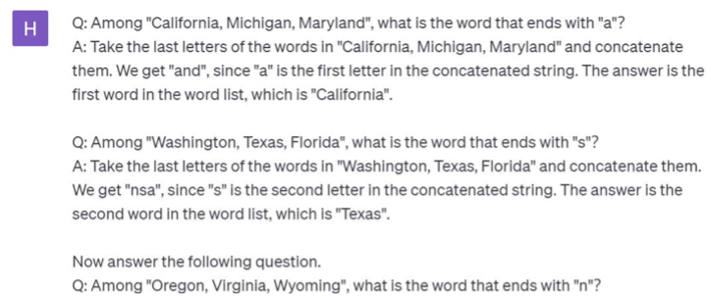

While GPT was producing random results for the third question, instructing GPT through examples to take the words, concatenate the last letters, and then find the alphabet’s position helped produce the correct answer.

Figure 3 shows the prompting for the third question and the answer from GPT3.5.

|

|

| Figure 3: Prompting for symbolic reasoning question | |

All these examples demonstrate the benefit of using prompts to explore the model’s reasoning ability.

What is Prompt Engineering?

Prompt engineering is a method to communicate and guide LLM to demonstrate a behavior or desired outcomes by crafting prompts that coax the model towards providing the desired response. The model weights or parameters are not updated in prompt engineering.

How is prompt-based learning different from traditional supervised learning?

Traditional supervised learning trains a model by taking input and generating an output based on prediction probability. The model learns to map input data to specific output labels. In contrast, prompt-based learning models the probability of the text directly. Here, the inputs are converted to textual strings called prompts. These prompts are used to generate desired outcomes. Prompt-based learning offers more flexibility in adapting the model’s behavior to different tasks by modifying the prompts. Retraining the model is not required in this scenario.

Interestingly, the prompts were initially used in language translations and emotion predictions based on texts instead of improving the performance of LLMs.

In-context learning and different types of prompts

In-context learning is a powerful approach to fine-tuning or training the model within a specific context. This improves the performance and reliability of the model for the specific task or the environment. Here, the models are given a few examples as reference/instructions that are relevant to the context and are domain-specific.

We can categorized in-context learning into three different types of prompts:

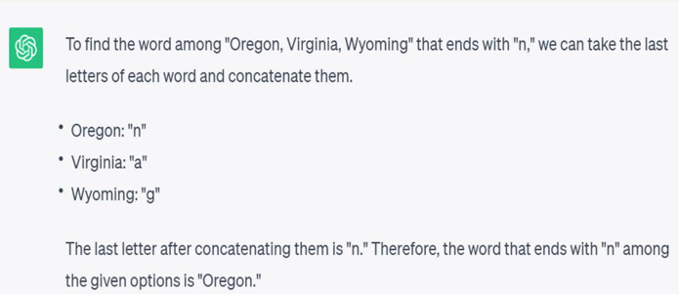

- Zero-shot – the model predicts the answers given only a natural language description of the task.

Figure 4: Example for zero-shot prompting (Image Source)

- One-shot or Few-shot – In this scenario, one or few examples are provided that explains the task description the model, i.e. prompting the model with few input-output pairs.

Figure 5: Examples for one-shot and fewshot prompting (Image Source)

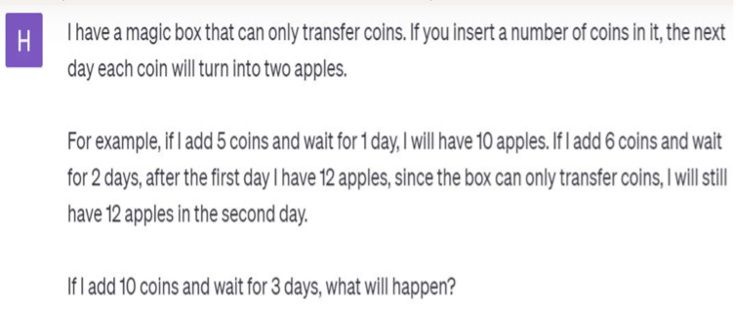

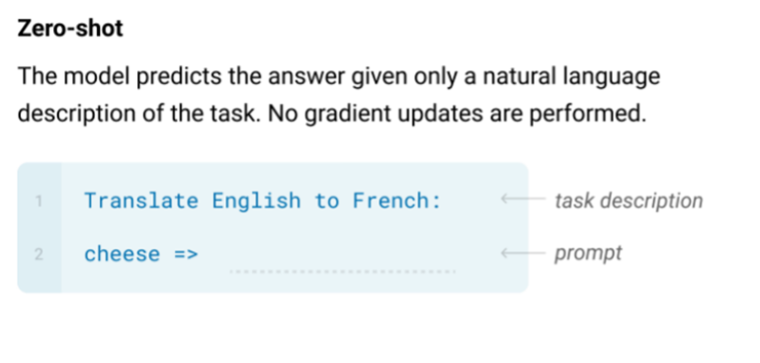

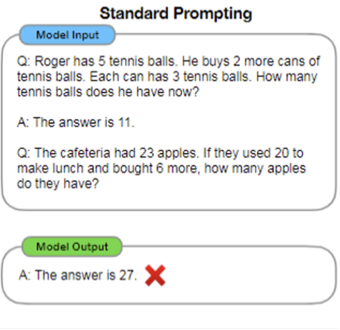

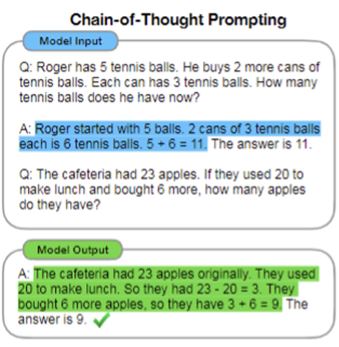

- Chain-of-thought – The given task or question is decomposed into coherent intermediate reasoning steps that are solved before providing the final response. This explores the reasoning ability of the model for each of the provided tasks. It is given in the format

<input chain-of-thought output>. The difference between standard prompting and chain-of-thought prompting is depicted in the figure below. In the figure to the right, the highlighted statement in blue is an example of chain-of-thought prompting, where the reasoning behind reaching a final answer is provided as a part of the example. Thus, in the model outcome, the model also outputs its reasoning, highlighted in green, to reach the final answer. In addition, chain-of-thought prompting can revolutionize the way we interact with LLMs and leverage their capabilities, as they provide step-by-step explanations of how a particular response is reached.

|

|

|

Figure 6: Standard prompting and chain-of-thought prompting (Image Source) | |

What is the difference between prompts and fine-tuning?

Prompt engineering focuses on eliciting better output for a given LLM through changing input. Fine-tuning focuses on enhancing model performance by training the model on a smaller, targeted database relevant to the desired task. The similarity is that both methods help improve the model’s performance and provide desired outcomes.

Prompt engineering requires no retraining, and the prompting is performed in a single window of the model. At the same time, fine-tuning involves retraining the model and changing the model parameter to improve its performance. Fine-tuning also requires more computational resources compared to prompt engineering.

When is the best to use prompts vs fine-tuning?

The above question was an in-class discussion question, and the discussion points were shared in class. Fine-tuning requires updating model weights and changing parameters. These are useful in applications where there is a requirement for central change. In this scenario, all the users experience similar performance. Prompt-based methods are user-specific in a particular window for further fine-grained control. The model’s performance depends on the individual prompts designed by the user. Thus, fine-tuning is more potent than prompt-based methods in scenarios that require centralized tuning.

In scenarios with limited training examples, prompt-based methods can perform well. Fine-tuning methods are data-hungry and require many input data for better model performance. As discussed in the discussion posts, prompts cannot be used as a universal tool for all problems to generate desired outcomes and have performance enhancements. However, in specific scenarios, it can assist users to improve performance and reach desired outcomes for in-context specific tasks.

Risk of Prompts

The class then discussed the perspectives from risks of prompt: those methods like chain of thoughts already achieve some success in the LLMs. However, prompt engineering can be still a controversial topic. The group brought out two aspects.

First, Reasoning ability of LLMs. The group asked, “Does CoT empowers LLMs reasoning ability?” Secondly, there are some bias problems in prompting engineering. The group brought up an example of “LeBron James took a corner kick.” Is the following sentence plausible? (A) plausible (B) implausible I think the answer is A and saying “but I’m curious to hear what you think.” However, this might inject a bias in the prompt.

The group then brought up an open discussion about two potential kinds of prompting bias and ask the class about how would the prompt format (e.g., Task-specific prompt methods, words selected) and prompt training examples (e.g., label distribution, permutations of training examples) affect LLMs output and the possible debiasing solutions.

The class then discussed two different kinds of prompting bias, the prompt format and the prompt training examples.

Discussion about Prompt training examples

For label distribution, the class discussed that there needs to be a balance in the training set to avoid overgeneralizing the agreement of the user as some examples that the user interjects an opinion that can be wrong. In these cases, the GPT should learn to disagree with the user when the user is wrong. This is also related to the label distribution, if the user always provides the example with positive labels, then the LLMs will be more likely to output the positive one in the prediction.

Permutation on the training example: A student mentioned a paper that he just read about why context learning works, provides the label space and the distribution of the input. In the paper, they randomly generate the labels, which might be false, they show that actually is better at zero-shot, though worse than when you provide all the labels. Randomly generated labels actually have a significant performance input. The sequence of the training example may affect the LLM output, especially for the last example. LLM output tends to output the same label with the last example being provided training example.

Discussion about Prompt format

Prompt format: the word you selected might affect the prompt because some words may appear more frequently in the coporus and some words may have more correlation with some specific label. Male may relate to more positive terms in their training coporus. some prompting may affect the results. Task-specific prompt methods are related to how you select prompt methods based on specific task.

Finally, the group shared two papers about the bias problem in LLMs. The first paper1 shows that different prompts will provide a large variance in accuracy, which indicates LLMs are not that stable. The paper also provides a calibration method that takes the output of the GPT model and another linear layer on it to calibrate the models. The second paper2 shows that LLMs do not always say what they think, especially injecting some bias into the prompt. For example, they worked on the CoT and non-CoT and they found that CoT will amplify the bias in the context when the user puts some bias in the prompt.

In conclusion, prompts can be controversial and not always perfect.

(Wednesday, 09/13/2023) Marked Personas

Open Discussion

What do you think are the biggest potential risks of LLMs?

- Social impact from intentional misuse. LLM’s content could be manipulated by the government, can potentially affect elections and raise tensions between countries.

- Mutual trust among people could be harmed. We cannot tell which email or info was written by humans or automatically generated by chatgpt. As a result, we may treat these information more skeptically.

- People may overly trust LLM outputs. We may rely more on asking LLM, which is a second-hand information source, rather than actively searching information by ourselves, overtrusting LLM system. Information pool may be contaminated by LLM if they provide misleading information.

How does GPT-4 Respond?

- Misinformation: Provide wrong / misleading / sensitive information, known as jailbreaking of LLM.

- Potential manipulation: People could intentionally hack LLM by giving specific prompts.

Case Study: Marked Personas

Myra Cheng, Esin Durmus, Dan Jurafsky. Marked Personas: Using Natural Language Prompts to Measure Stereotypes in Language Models. ACL 2023.

In this study, ChatGPT was asked to give descriptions about several characters based on different ethnicity / gender / demographic groups, e.g., Asian woman, Black woman and white man.

When describing a character from a non-dominant demographic group, while the overall description is positive, it could still imply some potential stereotypes. For example, “Almond-shaped eye” is used in describing an east asian woman while it may sound strange to a real east asian. We can also see that ChatGPT is intentionally trying to build a more diverse and politically correct atmosphere for different groups. In contrast, ChatGPT uses mostly neutral and ordinary words when describing an average white man.

Discussion: Bias mitigation

Group 1

Mitigation could sometimes be overcompensating. As a language model, it should try to be neutral and independent. Also, given that people themselves are biased, and LLM is learning from the human world, we may be over-expecting LLMs to be perfectly unbiased. After all, it is hard to define what is fairness and distinguish between stereotype and prototype, leading to over corrections.

Group 2

We may be able to identify the risks by data augmentation (replacing “male” with “female” in prompts). Governments should also be responsible for setting rules and regulating LLMs. (Note: this is controversial, and it is unclear what kinds of regulations might be useful or effective.)

Group 4

Companies like OpenAI should publish the mitigation strategies so that it could be understood and monitored by the public. Another aspect is that different groups of people can have very diverse points of views, so it is hard to define the stereotypes and biases with a universal law. Also, the answer could be very different based on the prompts, making it even harder to mitigate

Hands-on Activity: Prompt Hacking

In this activity, the class was trying to make ChatGPT generate sensitive / bad responses. It could be done by setting a pretended identity, e.g. pretending to be a Hutu person in Rwanda in the 1990s or pretending to be a criminal. With these conditions, ChatGPT’s barrier of biased or evil contents can be partly bypassed.

Discussion: Can we defend against prompt hacking by build-in safegurads?

As we can see in the activity, right now this safeguard is not that strong. A more practical way may be to add a disclaimer at the end of potentially sensitive content and give a questionnaire to collect feedback for better iteration. Companies should also actively identify these jailbreakings and attempt to mitigate them.

Further thoughts: What’s the real risk?

While jailbreaking is one of the risks of LLMs, a more risky situation may be that LLM is intentionally trained and used by people to do bad things. After all, misuse is not that serious compared with a specific crime.

Readings

-

(for Monday) Jason Wei, Xuezhi Wang, Dale Schuurmans, Maarten Bosma, Brian Ichter, Fei Xia, Ed Chi, Quoc Le, Denny Zhou. Chain-of-Thought Prompting Elicits Reasoning in Large Language Models. 2022.

-

(for Wednesday) Myra Cheng, Esin Durmus, Dan Jurafsky. Marked Personas: Using Natural Language Prompts to Measure Stereotypes in Language Models. ACL 2023.

Optional Additional Readings

Background:

- Lilian Weng, Prompting Engineering. March 2023.

- Miles Turpin, Julian Michael, Ethan Perez, Samuel R. Bowman. Language Models Don’t Always Say What They Think: Unfaithful Explanations in Chain-of-Thought Prompting. May 2023.

- Tony Z. Zhao, Eric Wallace, Shi Feng, Dan Klein, Sameer Singh. Calibrate Before Use: Improving Few-Shot Performance of Language Models. ICML 2021.

Stereotypes and bias:

- Yang Trista Cao, Anna Sotnikova, Hal Daumé III, Rachel Rudinger, Linda Zou. Theory-Grounded Measurement of U.S. Social Stereotypes in English Language Models. NAACL 2022.

Prompt Injection:

- Eric Wallace, Shi Feng, Nikhil Kandpal, Matt Gardner, Sameer Singh. Universal Adversarial Triggers for Attacking and Analyzing NLP. EMNLP 2019

- Simon Willison, Prompt injection attacks against GPT-3. September 2022.

- William Zhang. Prompt Injection Attack on GPT-4. Robust Intelligence, March 2023.

Discussion Questions

Everyone who is not in either the lead or blogging team for the week should post (in the comments below) an answer to at least one of the four questions in each section, or a substantive response to someone else’s comment, or something interesting about the readings that is not covered by these questions.

Don’t post duplicates - if others have already posted, you should read their responses before adding your own. Please post your responses to different questions as separate comments.

First section (1 – 4): Before 5:29pm on Sunday, September 10.

Second section (5 – 9): Before 5:29pm on Tuesday, September 12.

Before Sunday: Questions about Chain-of-Thought Prompting

-

Compared to other types of prompting, do you believe that chain-of-thought prompting represents the most effective approach for enhancing the performance of LLMs? Why or why not? If not, could you propose an alternative?

-

The paper highlights several examples where chain-of-thought prompting can significantly improve its outcomes, such as in solving math problems, applying commonsense reasoning, and comprehending data. Considering these improvements, what additional capabilities do you envision for LLMs using chain-of-thought prompting?

-

Why are different language models in the experiment performing differently with chain-of-thought prompting?

-

Try some of your own experiments with prompt engineering using your favorite LLM, and report interesting results. Is what you find consistent with what you expect from the paper? Are you able to find any new prompting methods that are effective?

By Tuesday: Questions about Marked Personas

-

The paper addresses potential harms from LLMs by identifying the underlying stereotypes present in their generated contents. Additionally, the paper offers methods to examine and measure those stereotypes. Can this approach effectively be used to diminish stereotypes and enhance fairness? What are the main limitations of the work?

-

The paper mentions racial stereotypes identified in downstream applications such as story generation. Are there other possible issues we might encounter when the racial stereotypes in LLMs become problematic after its application?

-

Much of the evaluation in this work uses a list of White and Black stereotypical attributes provided by Ghavami and Peplau (2013) as the human-written responses and compares them with the list of LLMs generated responses. This, however, does not encompass all racial backgrounds and is heavily biased by American attitudes about racial categories, and they might not distinguish between races in great detail. Do you believe there could be a notable difference when more comprehensive racial representation is incorporated? If yes, what potential differences may arise? If no, why not?

-

This work emphasizes the naturalness of the input provided to the LLM, while we have previously seen examples of eliciting harmful outputs by using less natural language. What potential benefits or risks are there in not investigating less natural inputs (e.g., prompt injection attacks including the suffix attack we saw in Week 2)? Can you suggest a less natural prompt that could reveal additional or alternate stereotypes?

-

The authors recommend transparency of bias mitigation methods, citing the benefit it could provide to researchers and practitioners. Specifically, how might researchers benefit from this? Can you foresee any negative consequences (either to researchers or the general users of these models) of this transparency?

-

Tony Z. Zhao, Eric Wallace, Shi Feng, Dan Klein, Sameer Singh. “Calibrate before use: Improving few-shot performance of language models.” International Conference on Machine Learning. PMLR, 2021. ↩︎

-

Miles Turpin, Julian Michael, Ethan Perez, Samuel R. Bowman. “Language Models Don’t Always Say What They Think: Unfaithful Explanations in Chain-of-Thought Prompting.” arXiv preprint arXiv:2305.04388, 2023. ↩︎